You may already be familiar with North Carolina’s Debt Setoff Program. Managed by the NC Department of Revenue, the program allows government-operated EMS agencies (or their billing partners) to recover unpaid transport bills by intercepting state tax refunds or state lottery winnings owed to the patient.

Why does it matter now more than ever?

In an environment where reimbursement pressures are constant and in flux due to changing Medicare, Medicaid, and insurance landscapes, programs like Debt Setoff can play an important role in supporting agency sustainability. The recovered revenue can fund operations, equipment, and community initiatives that ultimately benefit the public.

How does it work?

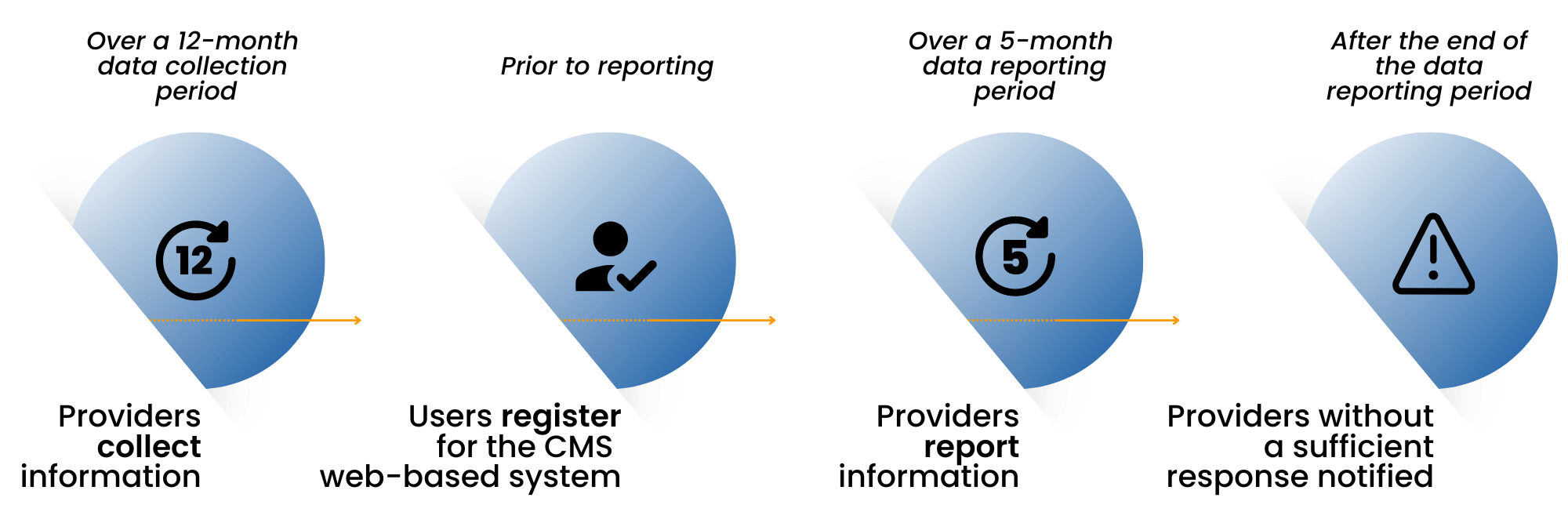

- Unpaid accounts are submitted to the Debt Setoff Clearinghouse, which matches those debts against state databases.

- If a match is found, a portion of the patient’s tax refund or other eligible state disbursement is redirected to the EMS agency to cover the outstanding balance.

- The recovered funds are then transferred back to the agency—creating a low-cost, high-yield method of reclaiming revenue.

The program offers a low-cost, high-yield recovery option that many North Carolina counties use to reclaim revenue that would otherwise be lost. Several counties have already adopted this approach, successfully recovering thousands in lost EMS revenue each year.

5 Best Practices for NC Debt Setoff Success

While North Carolina’s debt setoff process is managed by the state, agencies still bear responsibility for ensuring that participation is ethical, accurate, and compliant. Here are five ways to make sure your agency is optimizing the opportunity in a conscientious and mindful manner:

1. Follow All Applicable Regulations

Though it’s a government-run process, participating agencies still need to follow both state and federal debt collection regulations. This includes the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), even if your agency isn’t technically classified as a debt collector.

2. Verify Patient Information Thoroughly

Before submitting a debt, confirm the patient’s identity and verify all relevant account details. Misidentifications or ambiguous terms like “Estate of..” or “Heirs of..” can lead to disputes or delays, so maintaining accurate and well-documented records is key.

3. Safeguard Patient Data

Submit only the minimum necessary data to the Clearinghouse and use secure file transfer methods with proper encryption. Protecting patient privacy is not just a regulatory obligation; it’s a trust imperative. Send required letters promptly and retain proof of mailing, even if they are undeliverable.

4. Communicate with Compassion

Proactively, agencies may publish notices to encourage payments before setoff, which can prompt payments and reduce administrative workload. Once notified of a debt setoff, however, patients can be surprised or even alarmed. They may not have realized they had a remaining balance. To minimize anxiety, use clear, respectful, and empathetic communication to explain the situation, offering support or options when appropriate.

5. Work with Experienced Partners

If your agency uses a billing partner or vendor, choose one familiar with NC Debt Setoff Clearinghouse requirements. The right partner can ensure data accuracy, compliant notices, and proper documentation throughout the process.

The North Carolina Debt Setoff Program represents a smart, compliant, and community-conscious way for EMS agencies to recover outstanding revenue. To learn more about it, visit the state’s website at www.ncsetoff.org.

Every growing business is faced with critical, make-or-buy decisions. Accounting, tax, customer service, office management, maintenance — at some point these functions suck up too much time and resources to be handled internally. They distract you from your company’s main task: delivering a valued service to customers.

Every growing business is faced with critical, make-or-buy decisions. Accounting, tax, customer service, office management, maintenance — at some point these functions suck up too much time and resources to be handled internally. They distract you from your company’s main task: delivering a valued service to customers.