It’s becoming more likely that a solution or compromise to provide subsidies for lower income individuals to afford Affordable Care Act (ACA) insurance plans through State Marketplace Plans will not materialize. Although the exact impact is unknown, there are estimates as to what the reductions might entail.

Why does this matter to EMS agencies?

Typically, the highest reimbursement for patients served by EMS agencies comes from those with Commercial insurance plans. If individuals are unable to afford Marketplace insurance without some financial support, they are most likely to become uninsured, and the reimbursement for uninsured patients is only pennies on the dollar.

Let’s look at some of the early numbers since the subsidies have already lapsed for 2026, absent an unlikely deal achieved by Congress:

-

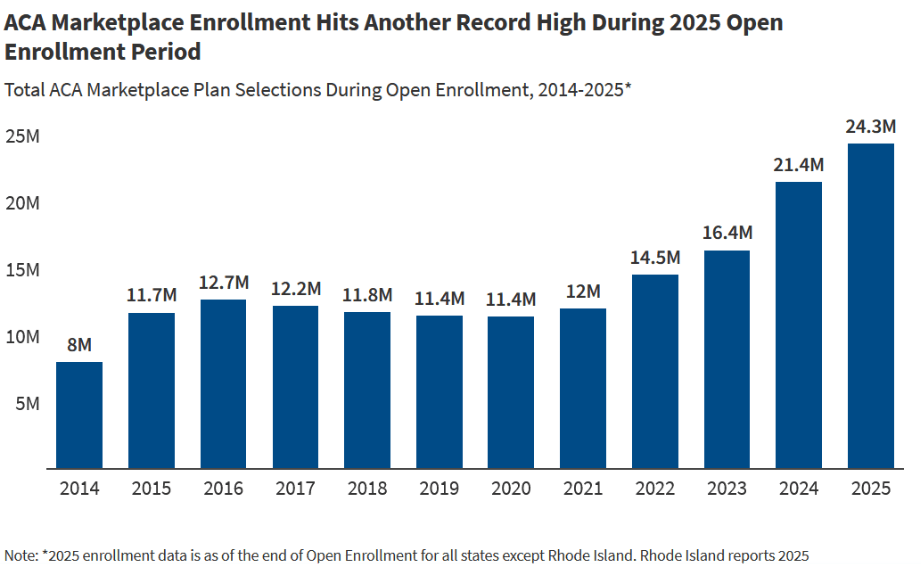

Per data published by CMS on January 28, 2026, about 23 million people signed up for individual market health insurance through one of the States’ Marketplaces.

-

Open enrollment ended on January 15, 2026.

-

The 23 million is down from 2025’s number of 24.2 million or about 5%, which is material but not substantial.

At a glance, it would seem like the revenue impact on any given EMS agency would be modest; however, a big concern isn’t just the 5% drop. Just as important is whether individuals begin to drop out of their plans by not paying their premiums if they find themselves unable to afford the monthly payments. Some third-party industry parties such as KFF have estimated that the ACA Marketplace drop would include close to 2 million people, possibly more.

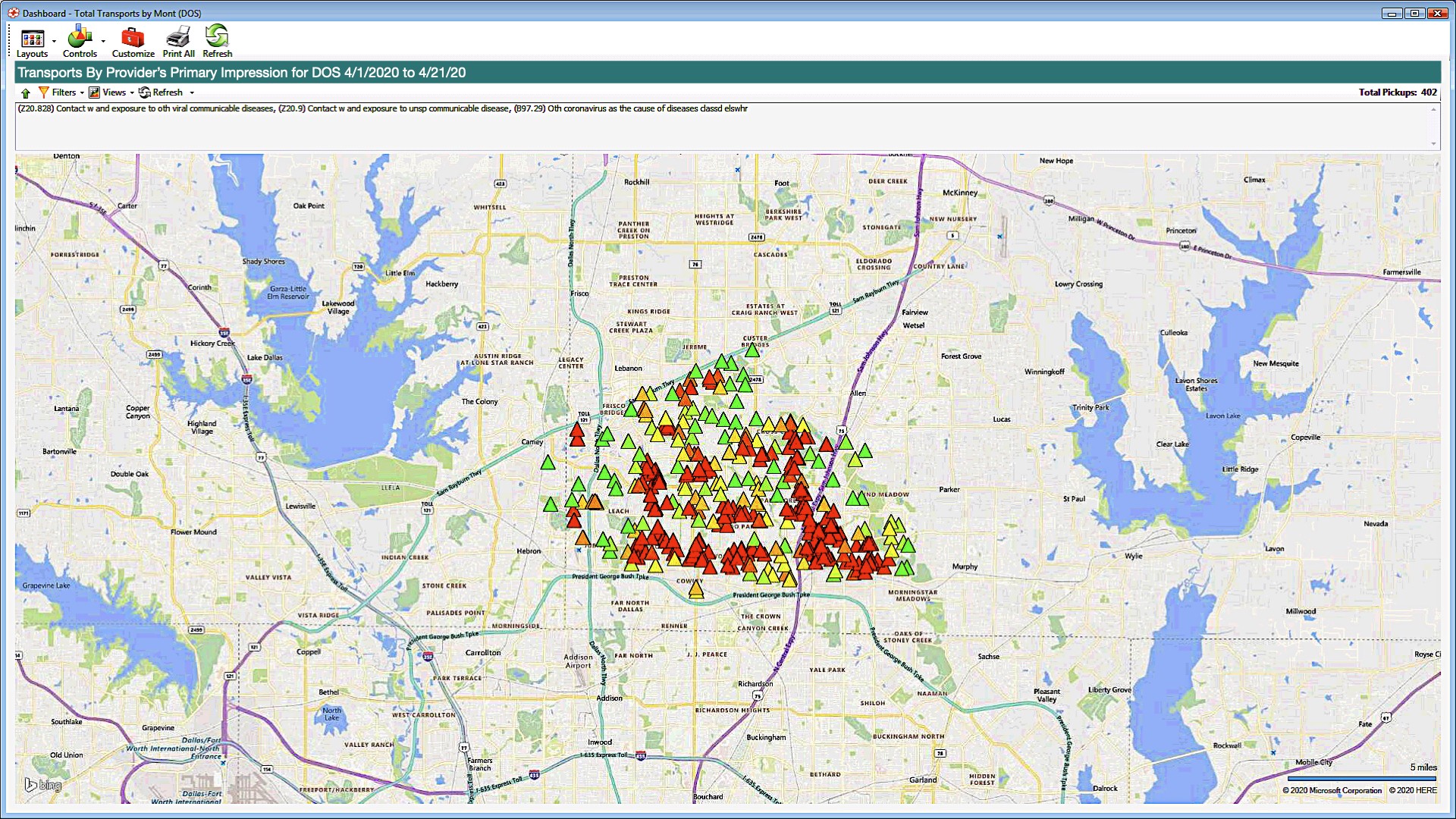

For any agency it’s not a simple as saying, “OK, if I plan for an 8% reduction in Commercially insured transports, that will give me a good idea of my at-risk revenue.” This is because some geographic locations have more enrollees than others. If you only look at the top 5 States with Marketplace enrollees, there is some tie to population, but not entirely.

| State | Marketplace Enrollees (2026 in millions) |

| Florida | 4.5 |

| Texas | 4.2 |

| California | 1.9 |

| Georgia | 1.3 |

| North Carolina | .8 |

Therefore, agencies located in these States would feel more of an impact. Additionally, locality within the State will have an impact. The people most susceptible to dropping insurance are typically lower-to-middle class individuals who make too much money to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough money to comfortably afford their various living expenses. As a result, they’re forced to make trade-offs about spending money on housing, food, healthcare, transportation and various other living expenses.

How can EMS agencies prepare?

Agencies are going to need to account for this shift in the insurance coverage of their patients. As an illustrative example, let’s use the 8% drop in Commercially insured individuals mentioned previously:

-

For an agency that does 10,000 transports annually and has 15% of its patients with Commercial insurance coverage, that translates to 1,500 commercially insured patients.

-

If 8% drop out, that’s 120 people.

-

If the average reimbursement for a Commercially insured patient is $1,250 versus $50 for someone without insurance, you could expect a drop of $1,200 for those 120 patients or a $144,000 annual decrease.

-

If your agency is four times bigger, that’s over a half million dollars in reduction.

You should be able to calculate the possible impact on your agency by asking your billing company to pull your numbers, similarly to above, and provide the impact at various reduced levels.

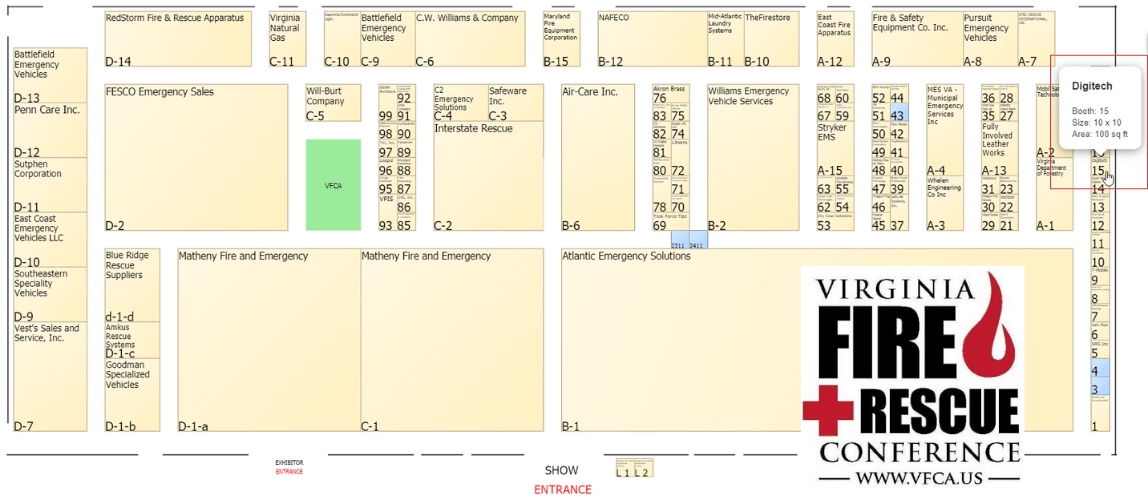

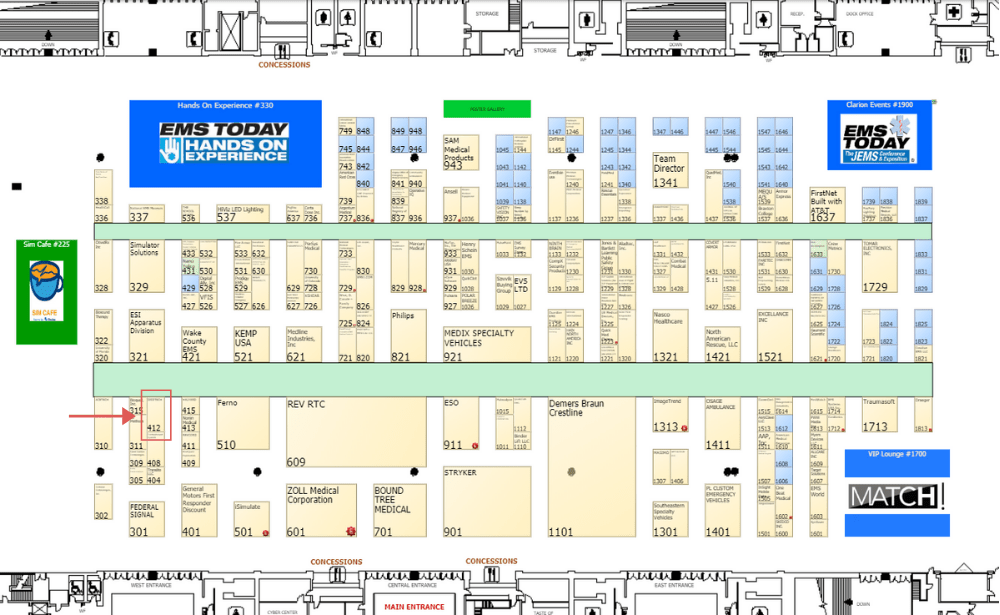

As Digitech has been stating for quite some time, we expect most of these impacts to occur gradually versus having an immediate drop; however, over the course of the next year, it is important to pay attention to the trends so that your agency can plan accordingly.

Perhaps a lifeline will be given to people relying on the Marketplace plans by Congress, but the current uncertainty suggests that a prudent approach is to plan for a gradual decline in revenue from your Commercially insured patients.

Every growing business is faced with critical, make-or-buy decisions. Accounting, tax, customer service, office management, maintenance — at some point these functions suck up too much time and resources to be handled internally. They distract you from your company’s main task: delivering a valued service to customers.

Every growing business is faced with critical, make-or-buy decisions. Accounting, tax, customer service, office management, maintenance — at some point these functions suck up too much time and resources to be handled internally. They distract you from your company’s main task: delivering a valued service to customers.